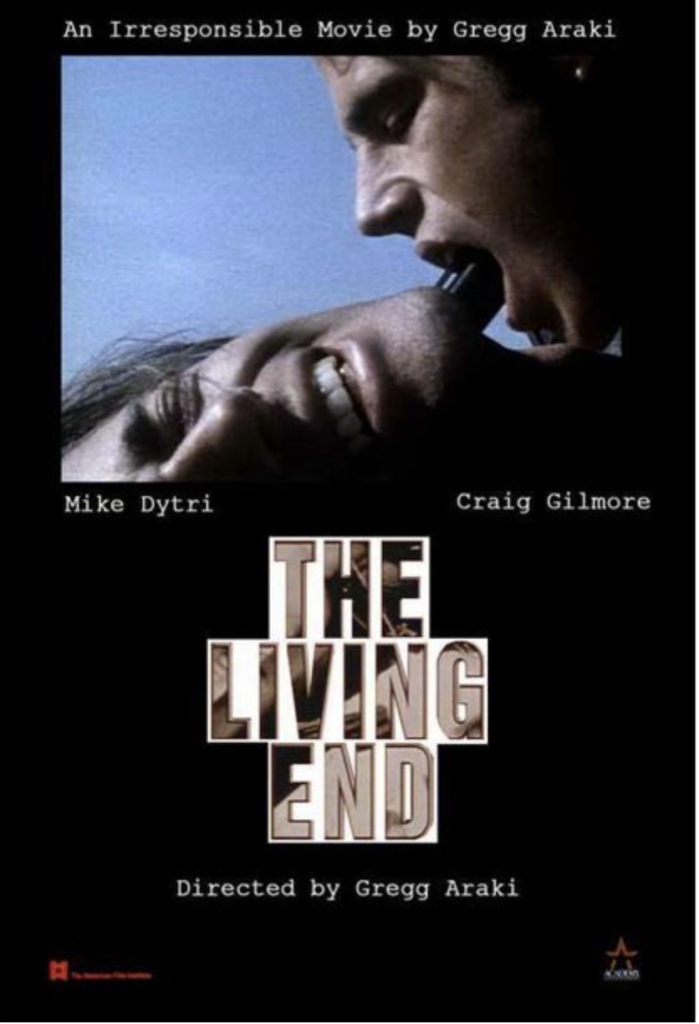

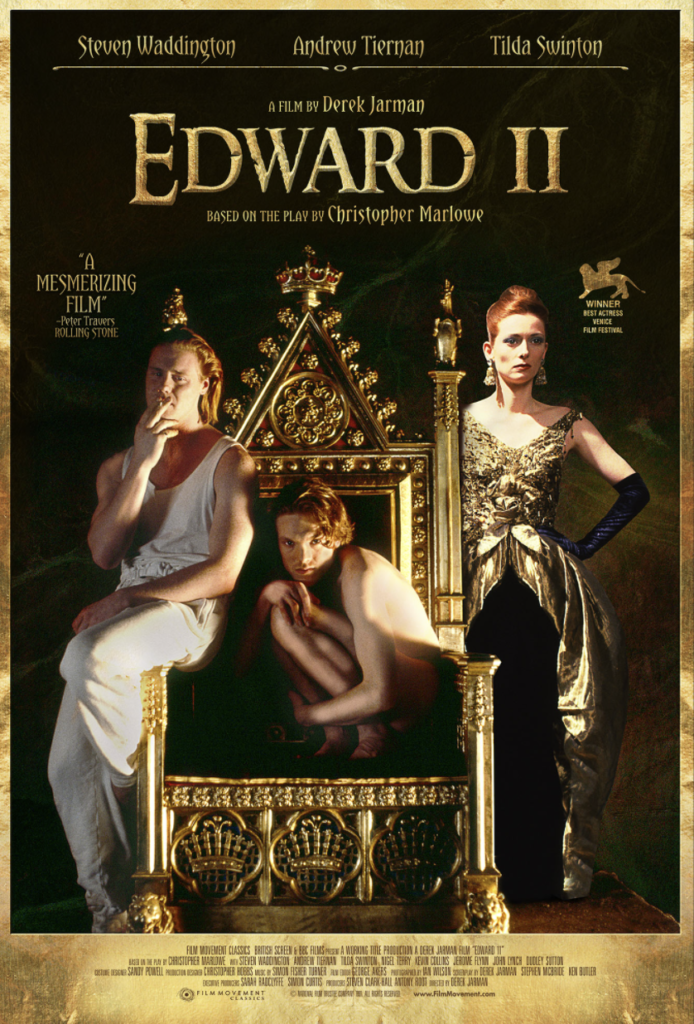

Inspired by the sudden influx of queer films, characters, and directors in 1992, film scholar and general badass B. Ruby Rich coined the term “New Queer Cinema.” From Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct to Derek Jarman’s Edward II, from Tom Kalin’s Swoon to Gregg Araki’s The Living End, it was hip to be queer!

Prior to this rush of queerness, gay and lesbian representation was limited, to say the least. For much of American film history, gay and lesbian actors and directors were often closeted, gay and lesbian subplots cleverly concealed to the average viewer, if they were there at all, while gay and lesbian characters usually existed solely for comic relief and/or to be killed off.

All of which means… hooray for queer culture in the 1990s!

Except for the fact that someone forgot to include women.*

If New Queer Cinema helped define art house cinema during the 1990s, the concept of lesbian invisibility helped define New Queer Cinema. Gay directors and gay actors were often male, and the films themselves often revolved around male desire. Even in terms of money, more funding went to gay male filmmakers rather than lesbian directors. All of this is still mostly the case and applies to television, as well, where lesbians and bisexuals have significantly lower representation on television than gay men (who, of course, are also under-represented, but that’s a separate issue).

There are a couple of reasons for this. Partly, as Frank Rich describes, there is “a misogynistic strain in America so durable that it’s still front and center in presidential campaigns.” We are all familiar with that. However, we should also note that “men, straight and gay, hold many more positions of power than straight and gay women do, and those men, whatever their sexual orientation, are going to favor their own stories.”

(Frank Rich was talking there about Hollywood, but as we know, it applies to everything.)

While straight women have Lifetime and Hallmark, gay women are still settling “for the crumbs of mainstream culture,” as Rich writes.

On a related note, let’s talk about The L Word. (See what I did there?)

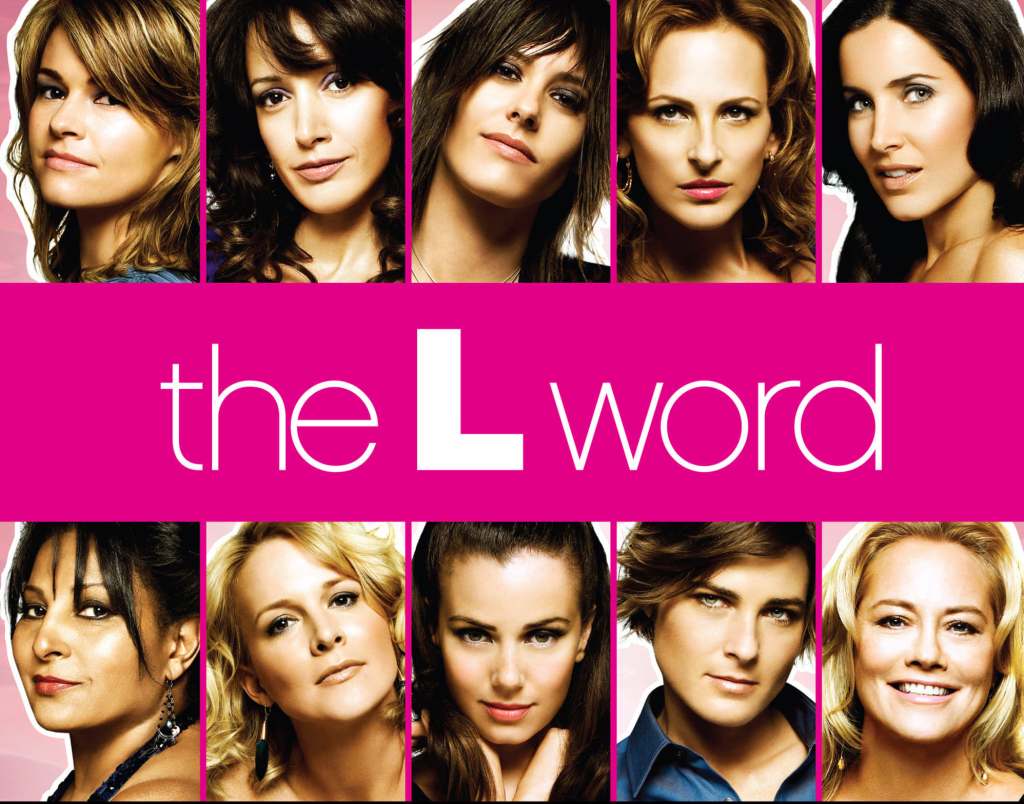

Premiering on Showtime in 2004, The L Word quickly gained notoriety because there were FINALLY! LESBIANS! ON TELEVISION! In a world where lesbians are still largely invisible, the existence of the first (and still only) lesbian ensemble drama was pretty fucking amazing. I mean, sure, it was trashy and possibly exploitative, but lesbians around the world cheered to see themselves on screen.

I mean, they cheered to see lesbians on screen. One of the main problems with the show dealt with issues of representation. As you can see above, most of the characters, much like with second-wave feminism, were of a particular body type (white, thin, pretty), class (middle and up) and sexuality (gay), but still — lesbians! One could almost overlook the exclusionary point of view because of what (and whom) the show did include.

By 2019, when The L Word: Generation Q (a sequel of sorts to the original, with some of the same central cast members and many new ones) premiered, lesbians weren’t as invisible anymore. In fact, they could be found on television shows as varied as Vida, P-Valley, Lost Girl, and Orange Is the New Black. However, despite the myriad of streaming platforms and networks allowing for almost every kind of niche programming, there still wasn’t another lesbian ensemble drama, so the rebooted L Word was cause for celebration — as was the fact that the show is significantly more diverse than the original! Hooray!

Maybe I’m a grouch, but I could not help but be disappointed by both seasons of Generation Q. Yes, the original show wasn’t known for complex characters or nuanced plots, but it felt like Masterpiece Theater when compared to this recent incarnation.

I had hoped that by 2019 (and then by 2021, for season 2) we would have gotten to a better place. Instead, as Judy Berman puts it, Bette, Alice, and Shane were still “living the same sparkly postfeminist fantasies” that made up the original version of the show, while the new characters, with their flimsy two-dimensional personalities, were tasked with issues such as class, race, and trans inclusion. Yes, there are disabled characters, trans characters, black characters, Latina characters, and so much more, but there often wasn’t much more to the characters than that one label or cause. For example, Micah Lee (Leo Sheng), who often feels like the token trans character, doesn’t appear to have any personality traits other having a crush on an unavailable neighbor and not wanting to be used as a token trans therapist at his new job.

Ah yes, tokenism, the definition of which includes “gay supporting characters” in its sample sentence, AS IF IT KNOWS.

Out of all the new characters, Finley (Jacqueline Toboni) is my favorite. Unfortunately, the issue with which she is tasked appears to be alcoholism. In typical L Word fashion, the writers handle this issue with a predictable blend of incomprehension, naïveté, and over-simplification. How exactly do we know that Finley is an alcoholic? There was no story progression, no depiction of a downward spiral, she just suddenly seemed to become an alcoholic. Her friends don’t seem concerned about it until suddenly they are organizing an intervention. Has Finley ever been to a meeting? When she got sober, how and why did she do it? Does she recognize it as a problem? What are the stakes?

While we do have Finley drinking a lot (although it’s not clear if it’s a lot a lot, other than the DUI moment), the intervention still feels like it comes out of nowhere. Finley argues that she drinks as much and as often as others in their twenties, something that could very well be true and which speaks to a larger problem, but the show skips over it entirely. (I mean, we could even take a sidebar to talk about alcohol consumption in the queer community as a whole. The fact that Shane owns a bar could be the perfect opportunity to take a deep dive!) Instead, the characters on the show, as well as the writers, appear not to appreciate how addiction works, which is especially amusing since one of the characters is a therapist and another is an alcoholic in recovery! Without complexity, both Finley and the show suffer.

Yes, the show should warrant some praise for tackling the problems of its past, but it still manages to repeat many of the same problems! For instance, while the original series had, to quote Candace Hansen, “Alice’s awkward and problematic stint chasing Papi through bars and clubs in a pre-gentrified East L.A. shot from a painfully white gaze,” the new series has Shane’s visit to a Black lesbian poker club, from which she is quickly kicked out after flirting with the girlfriend of the dyke-in-charge (Lena Waithe). The brief visit serves its purpose, however: Shane promptly appropriates the poker club idea and brings it to her mostly white clientele. At the very least, that’s cringe-worthy.

The show also seems to want to resolve the bi-phobia present in its earlier incarnation but Generation Q’s half-hearted attempted at a bisexual plot line, in which Alice is gifted a cisgender heterosexual male, is awkward at best. As Hansen writes, “framing a Black man as bumbling, smelly breathed, and willing to put up with Alice’s shame and indifference toward him is hardly progress.” So that’s also a disappointment.

Much like with the original version, butch characters are few and far between on Generation Q, which also feels, like the strange lack of nonbinary characters, to be a real missed opportunity. Rosie O’Donnell appears briefly as Carrie, in a role far more diminutive than O’Donnell deserves. To make matters worse, Carrie is, as Hansen puts it, “a self-loathing caricature of a messy fat butch.”

In a particularly uncomfortable scene, Carrie, in an unflattering suit and with tears streaming down her face, asks Shane and Tess if she is good enough.

“People,” she cries, “have always thought that I’m a problem.”

Maybe it’s not people, Carrie. Maybe it’s just The L Word?

Because there is another show on television that represents queer life in a completely different way. It isn’t a lesbian ensemble show because it’s only got a few lesbians (and are they even lesbians?). One of the underlying cruxes of the show appears to be the oppression of terms and labels, the dangers of limits and expectations, so it is appropriately hard to define the show.

Work in Progress is also on Showtime, it also has two seasons, and it’s unclear if it will have a third, like with Generation Q,…but that’s where the similarity ends. The complexity of the characters, the messiness of their relationships to each other, the struggles of mental illness, and the exploration of gender, sexuality, and identity, are all treated in ways vastly more nuanced and complex than either version of The L Word. In many ways, the shows are polar opposites of each other.

Abby, the star and protagonist of Work in Progress (the actress plays herself), portrays a butch struggling with depression, anxiety, and her weight, frustrated by a lifetime of feeling out of place and uncomfortable in her own skin. The show not only paints a complex picture of how young Abby shaped current Abby through well-placed flashbacks, as well as how culture at large has shaped Abby as a whole, it also uses the same opportunity to make observations about how dyke and trans cultures have evolved. In one sequence, for instance, we see a queer bar through many different incarnations, each one representing a facet of queer life at that time.

Shayna Maci Warner praises Work in Progress for “its ability to build a world from the ground up, with an aggressive, sometimes depressive political humor that works so well because it comes from lived experience. It can’t offer the delicious escapist fare of lesbians fucking amok in sun-drenched California lofts, but it provides honesty and unexpected hope in a dark world.”

The L Word, in contrast, just seems to remind us over and over of what we can’t have. Yes, it offers us lesbians, but somehow the fact that a “lesbian show” can’t do better feels even more depressing somehow. Abby feels real, which might be because the character is based on a real person. But surely the writers of The L Word know some actual lesbians?

*notable exceptions: Go Fish (Rose Troche, 1994), The Incredibly True Adventures of Two Girls in Love (Maria Maggenti, 1995), The Watermelon Woman (Cheryl Dunye, 1997), But I’m a Cheerleader (Jamie Babbit, 1999)

Recent Comments