“The death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.”

—Edgar Allan Poe

WARNING: Graphic photos and descriptions within.

Seventy-six years ago, almost to the day, a passerby discovered the body of 22-year-old Elizabeth Short in a vacant lot in Southwest Los Angeles. In what has now become the stuff of legend, Short’s body had been carefully prepared and displayed for maximum impact. Her face had been sliced open from the corners of her mouth to her ears, leaving her with a too-wide gash of a smile, while her entire body had been cut cleanly in half. Pieces of flesh had been carefully removed from her breasts and thighs, and her lower body positioned on top of her intestines, a foot away from her upper half. Her hands were raised above her head. The body had been drained of blood. Short’s entire body had been cleaned with gasoline, thus rendering it impossible to find any fingerprints. Police and reporters compared the body to a disassembled mannequin both because of the separated body parts and because of the pure whiteness of her blood-drained body. This comparison to a doll matters because, much like her life, Short lost her humanity that day.

The Black Dahlia murder is the most compelling unsolved crime Los Angeles has ever known. What Jack the Ripper is to London, the Son of Sam to New York, or the Zodiac Killer to San Francisco, the Black Dahlia is to Los Angeles. Significantly, however, unlike the other cases just listed, the name Black Dahlia refers to the victim, not the killer. This was a murder that is about a woman (all the more so because the killer was never found), but it has also become something else entirely. Elizabeth Short’s death provides a case study of how sensational news stories take on elements of fictional storytelling, blurring our ability to separate entertainment from news, reality from fiction. Despite the fact that Short’s murder took place in 1947, it has become a prescient indicator for the way we process spectacular death today.

Why is it that we know so much about her death—her mutilated corpse has arguably become an element of our cultural lexicon—while most identifying details about her life remain unknown? What does our response to her death tell us about the way we view murders of beautiful (white) women?

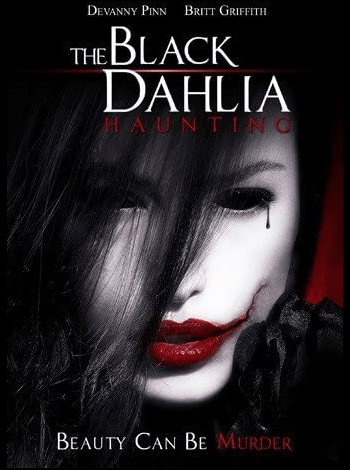

If, as Jacque Lynn Folton writes, “any story about the gruesome murder of a pretty victim is a national obsession” (2008: 99), no unsolved murder has become as much of a national obsession as that of Elizabeth Short, more commonly known as the Black Dahlia. The first time the Black Dahlia story appeared onscreen, it was in a 1975 made-for-TV movie entitled Who Is the Black Dahlia? directed by Joseph Pevney. Subsequent film and television adaptations, which often took great liberties with the truth, include the films True Confessions (Ulu Grosbard, 1981), The Black Dahlia (Brian de Palma, 2006), Black Dahlia (Ulli Lommel, 2006), The Devil’s Muse (Ramzi Abed, 2007), The Black Dahlia Haunting (Brandon Slagle, 2012), and the miniseries I Am the Night, directed by Patty Jenkins (TNT, 2019).

Elements of this story also appear in an episode of Hunter (“The Black Dahlia,” NBC, Jan. 9, 1988,) and in season one of Ryan Murphy’s American Horror Story (“Spooky Little Girl, FX, Nov. 30, 2011). Lynda La Plante’s book The Red Dahlia is a crime thriller in which a London killer duplicates Elizabeth Short’s murder. The story was adapted into season two of the British crime drama Above Suspicion (ITV, 2009-2012). There exist countless books and podcasts analyzing the unsolved murder, along with a tour industry devoted to exploring locations associated with Elizabeth Short, including the Black Dahlia Mystery Tour, courtesy of Dearly Departed Tours, and The Real Black Dahlia, courtesy of Esotouric Tours. There is even a video game entitled quite simply “Black Dahlia” and a death metal band, “The Black Dahlia Murder.” If it feels like Elizabeth Short is everywhere, you’re right.

Other than the chilling details of her body and what happened to it, about which any true crime aficionado probably knows too much, most other information about Short is hazy at best, a strange phenomenon given the extensive media coverage at the time. To this day, there is disagreement on everything from whether or not she was an aspiring actress, to whether she slept around or was a tease, to who gave her the nickname “The Black Dahlia.” Biographical information remains largely unknown.

The lack of biographical information, in contrast to the explicit familiarity many have with her death, is telling. As Helen Wheatley explains, spectacular death on screen can leave us with “a body, flayed, dismembered, bleeding and decomposing, but with no sense of how or by whom that body (or the person who once inhabited it) might be mourned.” This is precisely what we see here. In a perverse reaction, the more sensational the corpse, the less relevant the human. Despite the fact that Elizabeth Short lived and breathed for 22 years, the spectacular nature of her death has rendered her the stuff of fiction and legend. In many ways, she has become a dismembered doll, a plaything (a muse) for those seeking inspiration and entertainment.

For instance, even though there is no solid evidence Short was actually pursuing an acting career, this detail clings to her life story because it complements the story built around her. Ryan Murphy, when speaking about the Black Dahlia and why he added her to an episode of American Horror Story, explained that she “supposedly had a sexual addiction problem where she would put out and do the casting couch thing.” He also describes her as “obsessed with fame.” None of that has been proven. Nonetheless, in the “Spooky Little Girl” episode, Mena Suvari plays Elizabeth Short as an aspiring actress who offers a dentist sexual favors in exchange for fixing her teeth because she cannot afford to pay him. Ironically, in a review of the episode, Ron Hogan writes that the bloody gash of a smile the killer gives Short was “no doubt inspired by…Heath Ledger’s Joker makeup,” which is strange, given that Elizabeth Short was murdered thirty-two years before Ledger was even born. Elizabeth Short has been wiped out, replaced by narratives that make men (and their narratives) front and center.

Also important to Short’s legacy (and an additional explanation for the erasure of her personhood) is her association with film noir—an association also imposed by others after her death. The precise nature of her death, the precise nature, in fact, of her appearance—both before and after her death—and the related nickname (which may or may not have been imposed posthumously, a fact that seems like it would have been easy to ascertain at the time but which was not because details don’t seem to matter when it comes to a woman’s life) play an important role in creating yet another layer of theatricality, further distancing Short from “real life.” Regardless of whether the nickname came from the press or from friends, the name “The Black Dahlia” refers to a popular film of the era, The Blue Dahlia (1946), written by Raymond Chandler, author of the well-known noir classic The Big Sleep (published in 1939), and directed by George Marshall.

Katherine Farrimond points out that Short’s appearance too shores up this image, “her style of dress, dyed black hair and makeup…echoes the dark glamour of classic noir.” Farrimond goes on to emphasize that the date and location of Short’s murder further serve to reinforce the film noir trifecta of “beautiful women, death…and the mid-century urban landscape offered up in film noir and apparently crystallised in the Black Dahlia case” (35).

It would therefore be all too fitting that the Black Dahlia case would be referred to again and again in noir films (Sunset Boulevard) or neo-noir films (True Confessions and Devil in a Blue Dress), perpetuating the cycle of life imitating art and blurring the lines between the two. Is it any wonder that we too easily forget that Elisabeth Short was an actual human and not a figure of entertainment to be literally and metaphorically dissected? The associations to film noir make the murder (and the victim) feel more cinematic than real.

Ruth Penfold-Mounce and Rosie Smith write that two of the characteristics that define spectacular death are the “mediated/mediatized visibility of death and the commercialization of death” (39). The mediated quality of death is ever-present in the way death (regardless of whether real or fictional) has become a ubiquitous part of our cultural landscape. Devaleena Kundu points out that, “for a considerable number of television shows and programmes, death finds more than just a cursory mention, it is the central premise” (103). This is also the case with books, artworks, websites, podcasts, videogames, and music. In his essay “The Pornography of Death,” British sociologist Geoffrey Gorer argues that, as natural death becomes “more and more smothered in prudery,” violent death plays “an ever-growing part in the fantasies offered to mass audiences—detective stories, thrillers, Westerns, war stories, spy stories, science fiction, and eventually horror comics” (51).

Jacque Lynn Foltyn, in her article “Dead Famous and Dead Sexy: Popular Culture, Forensics, and the Rise of the Corpse,” summarizes Gorer’s argument that death had become as taboo in the twentieth century as sex had been in the nineteenth century. The result of this has been the proliferation of “a psychologically disturbed mass audience for unnatural, violent deaths as an entertainment genre,” a genre that Gorer described as pornographic “because of its brutality, exploitation, and distance from normal emotions like grief” (163-164). It is not just the corpses that are proliferating but the audience for them, as well.

The commercialization of death is evident in the profit margins of all those products. As Michael Hviid Jacobsen argues, the media landscape has turned death into a spectacle, “something to be observed, marketed, consumed, and discarded again after use, which makes death not all that different from other consumer items” (7, 9). Penfold-Mounce writes that the corpse in this “morbid space” is turned into a commodity to be exploited for profit: “As a consumable good, the corpse is being plundered through popular culture representations that subsequently reiterate the process of desensitization of the consumer (or viewer) of cadavers and death. It has become normal to market death and dead people to adults…as dramatic entertainment” (30).

When death is on a screen—movie screen, television screen, computer screen, or telephone screen—death equates with entertainment. Death, after all, compels, and the more violent and horrific, the higher the ratings and the greater the revenue. Or, as bell hooks writes, “The death that captures the public imagination in movies, the death that sells, is passionate, sexualized, glamorized, and violent.” And what is more passionate, sexualized, glamorized, and violent than the Black Dahlia?

Interestingly, Ruth Penfold-Mounce argues that “In both artwork and popular culture, the gaze is invited to look upon death and the dead in a realm that is defined by not being real life” (italics my own). She even continues by saying that “the unreal morbid space of popular culture encourages consuming the dead for pleasure or entertainment” (2018: 95, 96). Not only is the Black Dahlia murder significant because, as a result of the elements I listed above, it has taken on elements that make it feel more fictional than real, but the very way Short’s body was displayed makes it clear that the killer intended for us to consume her as an object, or, as she was originally described, a broken mannequin—and, most importantly, not as a human being.

Devaleena Kundu writes that “When a corpse is ‘exhibited’ for visual composition, it occupies a dual status—that of an object as well as that of a work of art. Once the viewer’s attention is drawn to the compositional aspects of the exhibited ‘corpse’…the aesthetic distance brought about by strategic positioning results in an improved appreciation for the corpse” (106). Kundu even likens bodies in crime shows to “pieces of homicidal art” (107). While she is specifically referring to television shows such as Hannibal, The Fall, Six Feet Under, True Detective, and Dexter, it is clear to see how her argument applies to the Black Dahlia murder, as well. Not only was Short’s body displayed as a work of art, but her corpse (and its arrangement) would inspire art, as well.

One of the leading suspects in her murder is George Hodel, and one of the primary arguments in favor of the Hodel theory is the link between Short’s dismembered body and the Surrealist artwork of Salvador Dali and Man Ray. The first person to argue that George Hodel’s friendships with various Surrealist artists helped to incriminate him was actually Steve Hodel, a former LAPD homicide detective and the son of George Hodel. In his book Black Dahlia Avenger (2003), Steve Hodel provides convincing evidence that his father murdered Elizabeth Short, dismembering and arranging her body as a three-dimensional Surrealist-inspired work of art.

In the book Exquisite Corpse: Surrealism and the Black Dahlia Murder, Mark Nelson and Sarah Hudson Bayliss build upon Steve Hodel’s theory, writing that the precise way which Short’s body had been arranged appeared reminiscent of the “beautiful but fragmented and anatomically distorted women” (9) common to Surrealist art, speculating that “the killer may have considered the artfully composed corpse his masterpiece and believed he was upstaging well-known artists of the day” (10). While many Surrealist works include disfigured or severed female bodies (not murdered!), there are clear comparisons in the book between Man Ray’s “Black Widow,” “Minotaur,” and “White and Black,” as well as Salvador Dali’s “Untitled – Set Design (Figures Cut in Three).” Man Ray had even been a close friend of Hodel’s.

Man Ray’s painting “Black Widow” (1915) depicts the black silhouette of a woman with her arms lifted above her head and her legs spread apart, identical to the positioning of Short’s arms and legs when her body was found. In his photograph “Minotaur” (1934), the arms are also raised above the head, angled just like in “Black Widow” or like the Black Dahlia corpse. Arms similarly raised can be seen in the photograph “Juliet on the Couch at 1245 Vine Street” (1945). There are even examples of Man Ray images with grotesquely large smiles (“Les Amoureux,” 1936 and 1970), like that found on the body, or of a woman sliced in parts (“White and Black,” 1929 and “La Jumelle, 1939), as Short had been. A woman in parts can also be seen in Salvador Dali’s “Untitled – Set Design (Figures Cut in Three)” (1942), as well as in Max Ernst’s “Anatomie als Braut” (1921), which translates to “Anatomy as a Bride,” all of which bear a chilling resemblance to the way Elizabeth Short had been disfigured, asking the question—did they serve as inspiration? Was Elizabeth Short arranged like a doll to further a Surrealist fantasy? Was there a killer who wanted us to see her as a work of art rather than as a dead woman? If so, the last seventy-six years only served to support that agenda.

Perhaps even more chillingly, Nelson and Bayliss go on to argue that Short’s body might have, in turn, provided inspiration for future Surrealist works. For instance, they write that the Black Dahlia murder might have inspired Duchamp’s photographic installation “Étant donnés” (1946-1966), since, as they point out using jarring image comparisons, “Duchamp’s unusual diorama shows clear similarities to crime-scene photographs of Elizabeth Short’s body” (124-125). In “Étant donnés,” the viewer peers through a peephole to discover a naked woman splayed upon the grass, her head in the shadows, her body arranged very similarly to that of Short’s.

While Marquard Smith, in his book The Erotic Doll: A Modern Fetish, writes that he is “suspicious of the connection” made between Duchamp’s artwork and Short’s body, he does point out that there are a number of “formal, iconographic equivalences,” such as the arrangement of the bodies and the way the composite parts are emphasized more than the entirety of either body. He even compares the open wound on Short’s torso—showing up as a black slash in the crime scene photos—to the vaginal opening in Duchamp’s figure—also seemingly a black slash—which, in turn, echoes the carved smile on Short’s face (286-287). While he insists that “mannequins and dolls are not human,” and that therefore the two cannot be compared or made equivalent (287), the point here is that Short was turned into a doll or a mannequin. The killer saw her that way and we continue to see her that way. So that alone is not reason enough to dismiss the similarities between the two.

The “art imitating life” pattern does not stop there. French photographers Pierre et Gilles shot burlesque dancer Dita von Teese as the murdered Elizabeth Short for the piece “Le Dahlia Noir -+ January 15, 1947” (2003), French for the Black Dahlia, followed by the date Short’s body was discovered. Teese lies corpse-like on the floor, covered in shredded paper, her hands and arms made to look severed, with the ubiquitous slash across her face, from edge of the mouth to cheekbone. Her eyes stare blankly at the ceiling. Her skin is made so porcelain white that she, perhaps even more so than Elizabeth Short, really does look like a doll or a mutilated mannequin. Most alarmingly, however, is the press release from the Parisian art gallery exhibiting the work in 2004, Galerie Jerome de Noirmont, which describes the image as Teese slipping “into the skin of James Elroy’s Dahlia Noir (The Black Dahlia).” Except, of course, it is not Elroy’s Black Dahlia. It is Elizabeth Short, an actual person. James Ellroy (with two L’s) wrote a book about her, The Black Dahlia, published in 1987. Once again, Short has been wiped out, replaced by narratives that make men (and their narratives) front and center.

Clearly a fan of The Black Dahlia mythology, Teese also did a photo shoot with photographer Steve Erle in George Hodel’s former home, known as the John Sowden House, where many believe Elizabeth Short was murdered, although this has not been proven. Erle describes the photo series as “Dita Von Teese photographed in Los Angeles at the infamous Black Dahlia House,” which is not at all the name of the house. We don’t know if she was ever even there. With her dyed black hair and brilliantly blue eyes, the resemblance between the two women is obvious and clearly a quality Teese chooses to emphasize. For her lingerie company, Teese even has “Black Dahlia” designs. In this example, Elizabeth Short has been wiped out, replaced by another woman’s narrative.

Teese’s career has been built on her beauty and sex appeal, so the implication is that there is something beautiful and sexy about a murdered woman. Again, the name of the photograph and the name of the lingerie is not “Elizabeth Short.” Rather, it is the name given to Elizabeth Short (by whom we do not know) that has taken on glamorous and evocative qualities, at least according to Teese. That this mystique is something worth recreating, selling, and buying turns a horrific murder into a commodity and makes the actual victim disappear.

Appropriately for Elizabeth Short and the way in which she has been romanticized and sexualized post-death, Ruth Penfold-Mounce, in her article “How the Rise in TV ‘Crime Porn’ Normalises Violence Against Women,” argues that women embody the “ideal victim,” largely because they are “pretty, white, young, and female” (2016). This pattern normalizes the idea that women are more vulnerable to violence and that female corpses can be things of beauty, even apparently when they have been horrifically dismembered. Why else would Dita von Teese want to recreate her? This concept of the “ideal victim” then, in turn, creates the “ideal drama,” with the female as the “linchpin for compelling shock driven visual tales using extreme, final, and often gruesome violence” (2016). It is the female corpse specifically that anchors narratives of gruesome violence, the female corpse that appears as the ultimate culmination of brutal murder, especially when she is young, pretty, and white.

In her article, “Bodies of Evidence: Criminalising the Celebrity Corpse,” Foltyn describes “corpse porn,” which she describes as a sexualized combination of violent death and an appalling corpse. Corpse porn, unsurprisingly, “overwhelmingly stars women, for the same reasons sex porn does, i.e. patriarchal obsession and control of mass media, and woman’s closer association with birth, sex, depravity, dirt, and death” (257). This merger of graphic violence and the erotic, especially when it comes to Elizabeth Short, is crucial toward understanding the significance of her murder upon the cultural consciousness. Ruth Penfold-Mounce explains that the autoptic gaze, a variation of the gaze of the camera, is “abject, voyeuristic, and forensically inclined, focusing on the eroticizing process of the cadaver as visual spectacle.” She goes on to emphasize that, in a variation of Laura Mulvey’s discussion of male/female differences in film narrative, the “victim’s corpse, who is predominantly female on forensic television shows, is a bearer and not a maker of meaning…Subsequently, even dead women become objectified other whereby the victim’s corpse is isolated, on display, and sexualized, and the spectator can indirectly possess her” (27).

In terms of Short, this means that, first of all, her corpse has been eroticized and turned into visual spectacle. We can see this even if only through Teese’s recreation of Short’s dismembered body, not to mention naming lingerie after her. Whoever killed Short saw her as an object, a doll to be arranged carefully for display in an empty lot, cleaned and scrubbed to remove any traces of blood or dirt, leaving her as close to an art form as he could manage. As the killer and arranger, he was the maker of meaning, much as every spectator who has projected a narrative onto the Black Dahlia has been, as well. It is telling that the press release for Pierre and Gilles’s exhibit credits James Ellroy with creating the Black Dahlia. In many ways, he, along with the murderer and the press, creating the myth of the Black Dahlia, a myth that we continue to perpetuate with every film adaptation, video game, miniseries, or tour—and this myth is so loud that it has drowned out the woman at the heart of it.

Rest in peace, Elizabeth Short.

Here is a link to a podcast in which I discuss Elizabeth Short, her murder, and the aftermath.

Bibliography

Cohen, Daniel, “The Beautiful Female Murder Victim: Literary Genres and Courtship Practices in the Origins of a Cultural Motif, 1590-1850,” Journal of Social History 31.2 (Winter 1997), 277-306.

Farrimond, Katherine, “Postfeminist Noir: Brutality and Retro Aesthetics in The Black Dahlia,” Film & History 43.2 (Fall 2013), 34-49.

Foltyn, Jacque Lynn, “Bodies of Evidence: Criminalising the Celebrity Corpse,” Mortality 21.3 (2016), 246-262.

Foltyn, Jacque Lynn, “The Corpse in Contemporary Culture: Identifying, Transacting, and Recoding the Dead Body in the Twenty-first Century,” Mortality 13.2 (May 2008), 99-104.

Foltyn, Jacque Lynn, “Dead Famous and Dead Sexy: Popular Culture, Forensics, and the Rise of the Corpse,” Mortality 13.2 (May 2008), 153-173.

Galerie Jerome de Noirmont, “Pierre et Gilles: Le Grand Amour Exhibition Release,” http://www.noirmontartproduction.com/1994-2013/exhibition-expo25.html.

Hogan, Ron, “American Horror Story episode 9 review: Spooky Little Girl,” Den of Geek, Dec. 1, 2011, https://www.denofgeek.com/tv/american-horror-story-episode-9-review-spooky-little-girl/.

hooks, bell, “Sorrowful Black Death is Not a Hot Ticket: bell hooks on Spike Lee’s Crooklyn,” BFI, Dec. 16, 2021, https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/features/sorrowful-black-death-not-hot-ticket-bell-hooks-spike-lees-crooklyn.

Jacobsen, Michael Hviid, “Introduction: The Whole World is Watching – Death in a Spectacular Age,” The Age of Spectacular Death, Michael Hviid Jacobsen, editor, London and New York: Routledge, 2020, 1-19.

Kundu, Devaleena, “The Aesthetics of Corpses in Popular Culture,” Death in Contemporary Popular Culture, Adriana Teodorescu and Michael Hviid Jacobsen, ed., London and New York: Routledge, 2019, 103-115.

Murphy, Ryan, quoted in Tim Stack, “American Horror Story: Ryan Murphy on the Black Dahlia and Violet,” Entertainment Weekly, Nov. 30, 2011, https://ew.com/article/2011/11/30/american-horror-story-ryan-murphy-spooky-little-girl/

Nelson, Mark and Sarah Hudson Bayliss, Exquisite Corpse: Surrealism and the Black Dahlia Murder, New York and Boston: Bulfinch Press, 2006.

Penfold-Mounce, Ruth, “Corpses, Popular Culture, and Forensic Science,” Mortality 21.1 (2016), 19-35.

Penfold-Mounce, Ruth, Death, the Dead, and Popular Culture, Bradford, UK: Emerald Publishing Group, 2018.

Penfold-Mounce, Ruth, “How the Rise in TV ‘Crime Porn’ Normalises Violence Against Women,” The Conversation, Oct. 24, 2016, https://theconversation.com/how-the-rise-in-tv-crime-porn-normalises-violence-against-women-66877.

Penfold-Mounce, Ruth, and Rosie Smith, “Resisting the Grave: Value and the Productive Celebrity Dead,” The Age of Spectacular Death, Michael Hviid Jacobsen, editor, London and New York: Routledge, 2020, 36-51.

Quigley, Christine, The Corpse: A History, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1963.

Smith, Marquard, The Erotic Doll: A Modern Fetish, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013.

Verdery, Katherine, The Political Lives of Dead Bodies: Reburial and Postsocialist Change, New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Your thought piece makes a lot of great points. I stumbled across this trying to find the location of where Short’s body was found, and instead left with your arguments ringing in my ears. It *is* obscene when Short’s murder gets co-opted into some male fantasy sex crime thing, as both Ryan Murphy and D V Teese continue to exploit her, while her whole life gets reduced to she did the casting couch and was a sex addict, when none of it is established. Good points, good article. I missed the warning regarding the crime scene photos, was not expecting to see that at all, and wish I hadn’t.