Do you remember the migrant caravans?

How can you not, right? You barely escaped with your life!

In 2018 and 2019, Trump couldn’t stop warning Americans about the large, organized caravans—full of criminals! rapists! gang members! terrorists!—that were headed straight from Mexican cities to destroy America.

Trump ranted about the caravans during spring 2018, the fall 2018 midterm elections, the weeks leading up to the State of the Union, even the State of the Union itself, declaring that these caravans posed a threat “to the safety of every single American.” Depending on the day, the caravans contained MS-13 gang members and/or “unknown Middle Easterners,” despite zero evidence about either.

The threat, much like Trump’s rhetoric, was unrelenting. The immigrant invasion was imminent! Without a wall, we were done for!

Ian Allen, for The Nation, writes:

“The current framing of the “caravans” came from white supremacists and other bad actors in the racist far right. It is now being written into our laws by officials in the Trump Administration, many of whom were recruited from Southern Poverty Law Center-designated anti-immigration hate groups like CIS and the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR). These allied constituencies are working together to create a toxic public debate that demonizes immigrants as ‘caravans’ of invading hordes, because this context enables them to escalate the immigration debate, militarize the border, and put brown-skinned kids in cages. None of this is rhetorical. Nor is it a mistake. It is, rather, the coordinated effort of an energized, dedicated group of extremist activists, who are employing sophisticated means of achieving their policy goals. And they are succeeding.”

So while the actual threat of the caravans may have been conjecture and spin, it still served a very real purpose: it galvanized the Republican base, translating directly into votes and new legislation.

Fear is no stranger to Republican talking points. In fact, it had been the theme of the Republican National Convention in 2016. During the convention, former Republican House speaker Newt Gingrich warned that major American cities were at risk of being lost to terrorists with weapons of mass destruction and that Hillary Clinton could have indirect links with Lucifer, a sentiment shared by Presidential candidate Ben Carson and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. Former mayor of New York City Rudolph Giuliani declared, “The vast majority of Americans do not feel safe. They fear for their children.”

In addition to reinforcing the legitimacy of the fear many felt, this also made those who still felt safe to wonder what they were missing.

Journalist Dylan Matthews describes Trump’s convention speech as “one of the darkest, most foreboding, and aggressively fear mongering speeches in modern political memory,” a description of a world “where citizens are living under constant threat of attack.” Despite the fact that this is not true, and “America has more or less never been safer,” fear was the capital and the Republicans were trading on it.

All of which begs the currently relevant question: why didn’t Trump rush to embrace the coronoavirus as manna from heaven, a unique gift that would allow him to justify all his xenophobic and nationalistic aspirations?

He could have whipped up the travel ban of his dreams! He could have shut down borders! He might even have been able to get more funding for his wall! He could have played up on the fear in which Republicans have been marinating for decades!

And yet—he didn’t.

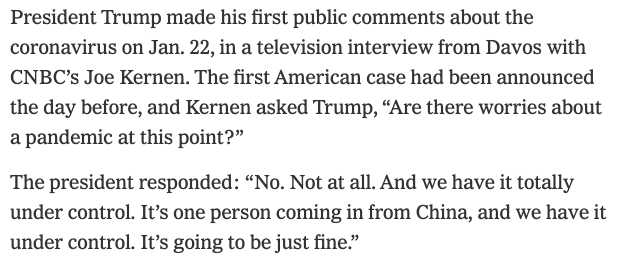

When briefed about the virus, he downplayed the threat. He tried to dismiss and assuage fear—the virus, after all, was a hoax. It was no big deal. In fact, it was already under control.

Strangely, the Republican party, usually defenders of expanding government overreach with tools like the Patriot Act, followed suit. Conservative commentators and politicians alike preached the necessity of maintaining status quo, of not being afraid, of conducting life as if there was nothing to see here.

Strangely, the Republican party, usually defenders of expanding government overreach with tools like the Patriot Act, followed suit. Conservative commentators and politicians alike preached the necessity of maintaining status quo, of not being afraid, of conducting life as if there was nothing to see here.

And yet, in earlier centuries, rulers dreamed of an outbreak so that they could experience absolute power. Why didn’t Trump get the memo?

During an outbreak, for instance, inspection could function ceaselessly, information about each individual’s life and death passing through representatives of power. In his book Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Michel Foucault observes that it was illness that was met with control, containment, and heightened regulation. With responses that foreshadowed the United States following 9/11, viral outbreaks, and specifically plague, provided opportunity for “the penetration of regulation into even the smallest details of everyday life.”

The infectious other was removed or excised, while those still healthy were regulated and contained. The physical self was compartmentalized and controlled—much as the biological self was classified and segregated—based on health, illness, susceptibility for illness, and proximity to infection.

Protocol for regulating and controlling the body was then repurposed for regulating and controlling cities. For example, towns were divided into districts, districts into quarters, quarters by roads and houses, and so on. These were methods of imposing quarantine and delineating zones of infection and safety. Each individual was meant to stay fixed in his assigned place. If he moved, it was at the risk “of his life, contagion, or punishment.”

The justification that outbreaks required this kind of “spatial partitioning and subdivision” was taken to its extreme point in order to restrict “dangerous communications, disorderly communities, and forbidden contacts.”

Doesn’t this sound like Stephen Miller’s fantasy?

Similarly, threats like 9/11 can also prompt institutions (government, medical, and military) to impose acts of containment and regulation in the name of security while encouraging citizens to submit willingly to this kind of regulation.

There is even a comfort to defining who is “us” and who is “them,” who belongs and who does not, whom to fear (and contain) and whom to support. Xenophobic impulses to limit outside threats—whether Ebola victims or Syrian immigrants or innocent Chinese—can be seen as retaliation to the heightened awareness of “leaky borders” exacerbated by an increasingly networked society.

And yet, to return to the initial question: Trump dropped the ball on the gift that could have kept on giving. Why? Why miss an opportunity to capitalize on fear that could have led to greater power and control for him and his party?

The answer, ironically, goes back to that same fear that fueled the caravan talking points and the 2016 Republican Convention. It is not that conservatives see threats more clearly than the rest of us. It is that the conservatives, quite often, are cowards. They don’t process information properly because they are always in fight or flight mode. Critical thinking, naturally, is one of the first things to go.

The first response of the coward is always denial. In order to square their permanent feelings of insecurity, they have to make themselves believe that issues are always someone else’s problem or someone else’s fault. They stay on the side of the status quo, and they can convince themselves of literally anything from the righteousness of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson to the existence of an afterlife, as long as there is something in it for them.

If you compare the responses of right wing governments all over the world you will see the same thing: denial, followed by panic, followed by anger. But they will never accept the blame for any of it.

It is precisely because the coronavirus is actually a problem that Trump could not deal with it. That Republicans avoided it. It is much easier to spread fear about things that do not actually deserve them. Things that do actually deserve fear, like our current situation or climate change, for instance, conservatives ignore. After all, fear is a tool for control, not for constructive action.

If you want a plan, you need Elizabeth Warren.

This is brilliant. Simply brilliant. ????????

Thank you!

Excellent article. The comment that resonated with me, because it supports my long held opinion, is “as long as there is something it for them.” These people, Trump, et.al., know, understand, and hold dear words and concepts like “me”, “us”, and “mine”. The notion of the larger “we” is not part of their awareness nor their concern.

They fight for “me”, while “we” are on our own.