Telemachus is a figure in Greek mythology, the son of Odysseus and Penelope, and a central character in Homer’s Odyssey. The first four books of the Odyssey focus on Telemachus’s journeys in search of news about his father, who has yet to return home from the Trojan War.

In addition to describing the many journeys of Odysseus, the Odyssey also tells the tale of Telemachus, growing up with his mother Penelope and becoming a man. The Odyssey is also, as argued by Mary Beard in her book Women & Power, the first recorded example “of a man telling a woman to ‘shut up.’” More specifically, Beard writes, “telling her that her voice was not to be heard in public.” The man is Telemachus, and despite his youth, he tells his mother to go upstairs, to refrain from speaking in public, and that specifically “speech will be the business of men, all men, and of me most of all.”

Beard points out that not only is this one of the earliest examples of a man sending a woman (and her voice) out of the public sphere, but it is also a demonstration of an integral rite of passage for a boy entering adulthood: telling a woman to shut up.

In February 2017, Senate Republicans silenced Elizabeth Warren as she was reading a letter written in 1986 by Dr. Martin Luther King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, during the confirmation hearings for Attorney General Jeff Sessions. The letter had originally been written by King to protest the 1986 nomination of Jeff Sessions to federal judge. Ironically, King’s letter had also been silenced – by Senator Strom Thurmond, who blocked it from being entered into the congressional record.

When Warren tried to read the letter on the Senate floor, she was blocked by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who invoked a rule meant to silence senators who are demonstrating “conduct or motive unworthy or unbecoming a senator.” When Warren asked for permission to continue, McConnell refused. When Warren appealed, the Senate voted 49-43 that she had violated Senate rules, barring her from speaking until the nomination process was over.

This became the famous “Nevertheless, she persisted” moment, when McConnell’s attempt to silence Warren, claiming that she had violated the rules, she had been warned, and still, she kept trying, leaving Warren to read the letter on a Facebook live video that has over 13 million views.

Many argue that McConnell’s attempt to silence Warren backfired, turning her into a social media sensation and launching “Nevertheless, she persisted” into the cultural lexicon. Unfortunately, I would argue that this pivotal moment foreshadowed the end of Warren’s presidential campaign.

Yes, Warren’s delivery of the letter went viral. Yes, it acquired millions of views and even more fans, but the significance of the required outlet cannot be ignored. Warren was silenced in the Senate (her workplace) and sent to Facebook (social media, “tool of the masses”). Sure, she got a lot of views and an enthusiastic response, but the point remains: she was silenced in her workplace. She was silenced in Washington, DC, her recitation of the letter relegated to cyberspace. In the Senate, she was told to sit down and shut up.

Mary Beard continues: “For a start, it doesn’t much matter what line you take as a woman, if you venture into traditional male territory, the abuse comes anyway. It is not what you say that prompts it, it’s simply the fact that you’re saying it.” It is telling that other senators, including Bernie Sanders, were allowed to read from the same letter and not excluded.

The audacity is not the content of what Warren was reading. The audacity is that she had the temerity to open her mouth at all.

Both Hillary Clinton and Elizabeth Warren have been accused of being “shrill,” of having strident voices, aggressive voices, condescending voices, but really, the implicit message is that any voice they would have—any voice that conveyed ideas and opinions—is too loud because they really should stop speaking.

A brief collage:

![]()

![]()

A few days ago, shortly after Warren dropped out of the Presidential race, Megan Garber described for The Atlantic how America had punished Elizabeth Warren for her competence. Garber quotes a woman who liked Joe Biden but felt he was too old to be president. Pete Buttigieg, on the other hand, was “well positioned,” with a “gentle approach” the country needed. Warren, however? This woman said she wanted to slap her whenever she heard Warren talk, even if she agreed with Warren’s ideas.

To clarify: the problem is not Warren’s content. The problem is that she’s speaking.

Kelli Maria Korducki recently wrote an essay for Forge entitled “Why High-Achieving Women Pretend Their Lives Are a Mess.” For these women, their “achievements aren’t accidents,” but they cannot let on how much they care, shrugging off accomplishments as lucky breaks. These women are successful but also bumbling enough to be “relatable” and “nonthreatening.” The kind of women with whom, if they were a man, you’d like to have a beer.

Significantly, Korducki writes: “On account of her smarts and circumstances, the Hot Mess gets that her success needs to look a little bit like an accident in order not to garner resentment. Her messiness is equal parts internalized misogyny and compensatory measure.”

Warren, in contrast, refuses to be a mess. She refuses to pretend to be a mess. She refuses to pretend that her success is an accident. Her image, in contrast, is that of competence, knowledge, and qualified experience.

How dare she, amirite?

A profile of Warren in Boston Magazine from April 2017 describes her as the “new face of the Democratic Party and a favorite for the 2020 presidential race.” And yet, surprisingly, confusingly, infuriatingly, the headline of the article is: “Why Is Elizabeth Warren So Hard to Love?”

Despite listing Warren’s various accomplishments, describing her as “more than any other Democrat” the one brave enough and tough enough to stand up to Trump, “the antidote to your despair,” and the “answer to Trump and Trumpism,” journalist Andy Kroll quickly establishes that an interview with Warren is unusual, as if this point should be just as significant as the others. An interview with Warren, you see, “isn’t so much a conversation as a stump speech,” he complains.

Apparently, while being the Democratic Party’s answer to Trumpism, she should also make time to chat more, to listen to the journalist’s ideas, even if she’s the one being interviewed. After all, shouldn’t an interview with a presidential contender be a 50/50 casual conversation, as least when the contender is a women?

I’m surprised no one told her to smile.

Then there’s the issue of “electability,” perhaps the concept most responsible for giving Americans permission to vote for Bernie Sanders or Joe Biden or Pete Buttigieg rather than Elizabeth Warren, even if, as they insisted, she was their top choice. Garber, in a different article for The Atlantic entitled “Sexism Is Other People,” writes that even though “electability” masquerades as a “benign and objective concern,” it is nothing less than sexism. While it may be a different sexism than the one that fueled the chants of “Lock her up!” so callously directed at Hillary Clinton (who has still not been found guilty of anything), it might actually be worse. This new kind of sexism is more insidious. As Garber argues, “It is figuring out, day by day, how to maintain plausible deniability.”

I’m just being pragmatic, really. I’m not a misogynist, really. I’m not sexist, really. I’m just being strategic. Really! I’ll vote for the white dude. Any which one will do.

Electability is just as vague and problematic as another word that gets thrown around in similar contexts: likability.

It is significant that the very first question of Kristin Gillibrand’s campaign for president was about her likability: “A lot of people see you as pretty likable,” a reporter observed, asking if Gillibrand found that to be a “selling point.”

Amanda Hunter, research and communications director at the Barbara Lee Family Foundation, which supports women in politics, argues that “voters will not support a woman that they do not like, even if they believe she is qualified.” In contrast, “they will vote for a man that they do not like if they believe he is qualified.”

And what makes a woman unlikable? If she’s ambitious.

The nerve!

“While you’re at it,” Garber writes, “you can also point to all the studies that have highlighted the ways women politicians are punished for their ambition. You can point to the countless examples of women in public being told to be quieter, to be more accommodating, to take up less space. You can mention so much more.”

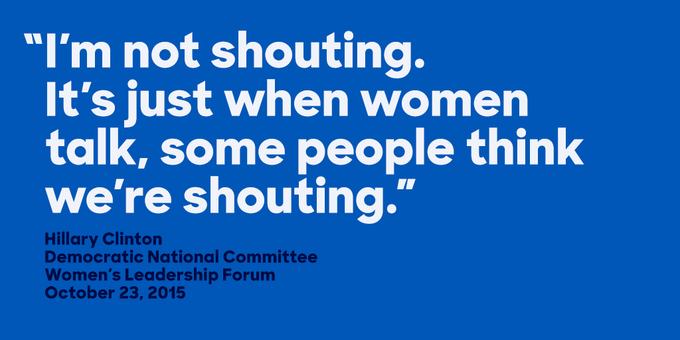

Or, as Bob Woodward explained about Hillary Clinton, one of her weaknesses revolves around her “style and delivery” because, naturally, “there is something unrelaxed about the way she is communicating,” because she “shouts.”

Clinton herself, having heard this critique many times before, responded: “I’m not shouting. It’s just when women talk, some people think we’re shouting.”

As Mary Beard already established with Telemachus, this is nothing new. The frustrating part is that it won’t stop. Despite all the superficial progress women have made over the years, it still seems inherently problematic when they want, you know, to talk.

A 1926 survey about talk radio preferences found that, by a margin of 100 to 1, respondents wanted male announcers. Women, you see, are “too enthusiastic” and “too patronizing,” unable to “strike the proper balance of emotions” or to “sound appropriately friendly without overdoing it.” When women tried to sound steady and controlled, they sounded “forced and unnatural.”

A documentary about the early use of women as telephone operators The first telephone operators were boys, who were criticized for being “rude and abusive,” as well as chaotic – wrestling matches, cussing, spitballing often filled the rooms. Naturally, these boys were replaced with women, who were much more thorough, organized, efficient, and well-behaved. However, in order to be properly prepared for the job, these woman also had to undergo vocal training to make their voices more deferential and docile.

Maggie Astor, in an article for the New York Times entitled “‘A Woman, Just Not That Woman’: How Sexism Plays Out on the Trail,” tells the story of Representative Madeleine Dean, recently elected to the House from Pennsylvania. Dean had an aide stand in the back of the room during campaign events, “holding up a cardboard sign with a smiley face to remind her to shift the serious expression she naturally wore while listening to voters.”

Sure, we can come up with many different reasons for why Warren’s campaign did not succeed, for why the primary is down to two elderly white men. We can hide behind concepts such as “electability” and “likability,” but the truth remains: she is too female.

And if she’s female, we all know what she should do. She needs to shut up.

To unruly women everywhere, those of us who have the audacity to have an opinion, to succeed and not be a mess, it’s on us now. We must persist. We must speak up. We must refuse to sit down. It is time to have voices that cannot be silenced.

I SO wanted Warren to stay in the race as long as she had the money to do so just to give a giant ‘f*ck YOU’ to male patriarchy. What this election has revealed about America is that not only is it not ready for a woman to lead it, but is intent on going about the process in a manner filled with unnecessary vitriol. How DARE she have a viable plan for everything? How DARE she be competent? I hope she runs again. She still has my vote waiting!

I agree and it’s disgusting. I just gave money last week, hoping others would do the same.