In honor of Marilyn’s birthday (and she is always Marilyn to us, never Miss Monroe), an essay from my archives:

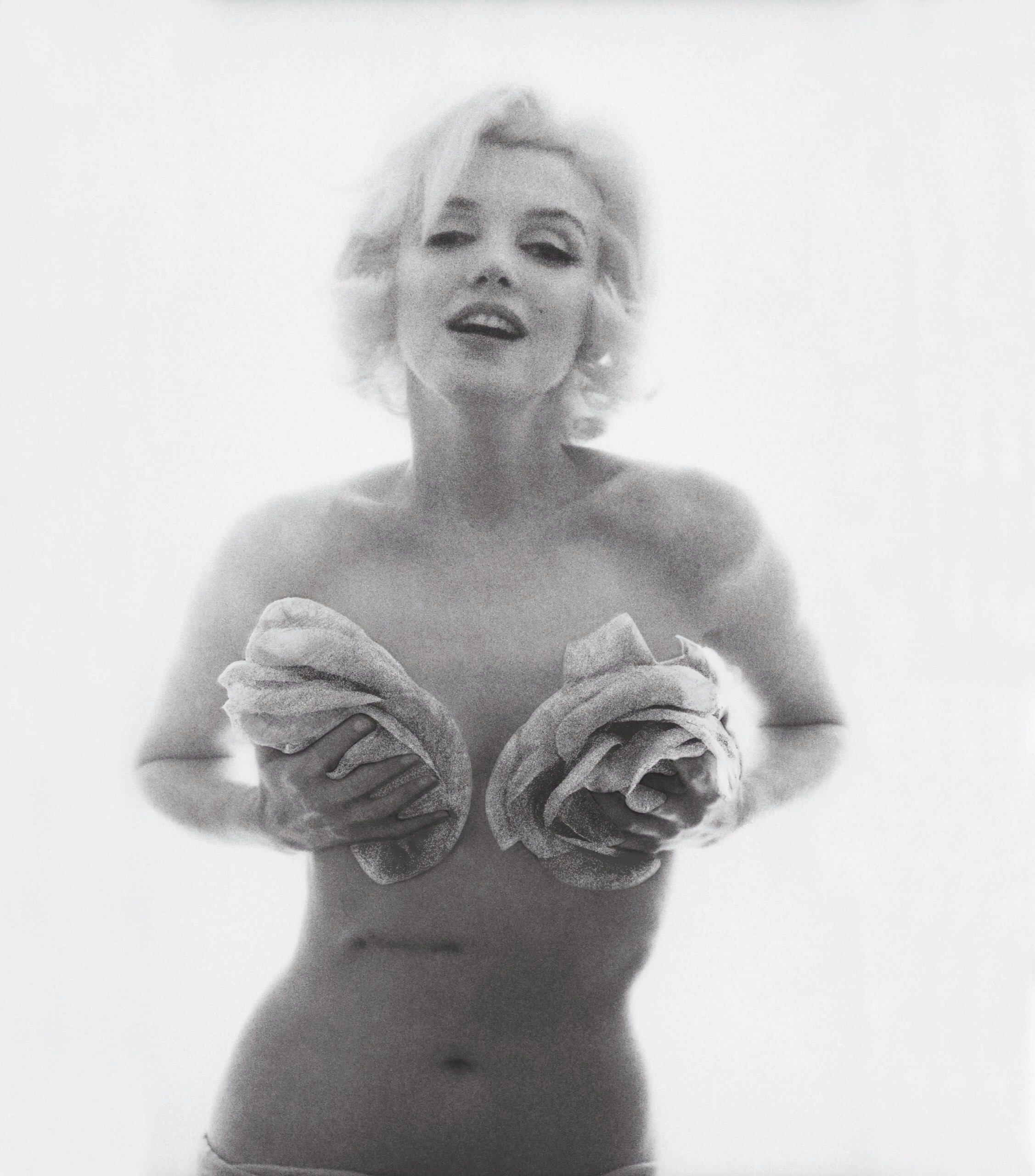

Six weeks before she died, Marilyn Monroe did a photo shoot with Bert Stern for Vogue magazine. These photos show a Monroe more natural, more exposed than ever before. Instead of the artificially perfect and rigid glamour more suited to a star of her status, her hair is casually tousled, and her lips often open—some say to hide a determined chin, others that it was a trick to make the shadow of her nose seem shorter—but the effect is fundamentally seductive. And that scar slashed across her abdomen?! It was rare for a star of that era to pose with such abandon, but Monroe did it without hesitation. She seemed determined to confront you with her self, perhaps in an attempt to move away from the artifice that imprisoned her during her films.

Marilyn Monroe was one of the last studio stars, if not actually the last, Jeanine Basinger argues. As a result, Monroe’s image was constructed via carefully planned magazine covers and glossy press photos, and perhaps more than her film roles, it was these photos that made her a star. Basinger writes, she was “a phenomenon of photography more than film,” and photo shoots provided the control Monroe lacked during filming. “The photographers come, it’s like looking in a mirror,” she explained. “They think they arrange me to suit themselves, but I use them to put over myself.”

Monroe spent a lot of time learning how to move her body, and this came through in the expert way she maneuvered both camera and photographer. Photographer Eve Arnold describes Marilyn as being in total control: “She knew a lot about cameras and I never met anyone who could make them respond the way she did. So she got what she wanted, because she wasn’t under all the kinds of pressures she felt during a film-shoot…With me, she was in charge of the situation.” Richard Avedon says, “She gave more to the still camera than any actress—any woman—I’ve ever photographed,” while Bert Stern describes Monroe as “more of a partner” than he had expected.

Monroe had the little things down, the blonde hair that got blonder as her persona evolved, a strict preference for wearing white, black and tan in order to set off her colours, but she also had a complex understanding for how/what a picture can make people think. Eve Arnold writes that Monroe “would study the stars’ images in Movie Mirror, Photoplay, or Screen Gems” in order to become “familiar with every gesture, every plucked eyebrow, every dewy eye.” Monroe would also insist on the right to veto any images she did not like and would spend hours going over the results of her shoots, crossing out (or even destroying) the images which she disliked. While her directors would tell her not to think, just to “do it” (John Huston) or “All you have to do is be sexy, dear Marilyn” (Laurence Olivier), the photo shoots offered Monroe the opportunity to create the roles she really wanted to play.

A template of her own construction, Monroe, like other auteurs, built a career not on referencing others, but on referencing herself. Though her film roles changed, S. Paige Baty writes that there remains the sense that Monroe was mediating “the very content and form of representation itself…a figure always already an artifice or construct, that is, a self-referential representation.” In the Seven Year Itch, we get one of those self-referential moments, when Sherman (Tom Ewell) jokes about the blonde in his kitchen, saying “Maybe it’s Marilyn Monroe!” Her character in the film (named solely “The Girl”) is nothing more than a caricature of what people would expect from Monroe—ultra-blonde, ultra-innocent, and ultra-desirable—an actual name unnecessary, since everyone already knew who she was: Marilyn Monroe.

Similarly, her character in The Misfits was also based on Monroe herself. In an especially cruel moment, her character spots the inside of a closet door, on which are taped six glamorous pictures of Marilyn Monroe, including the famous Seven Year Itch still with the white dress billowing up. When Guido (Eli Wallach) looks at the photos, Roslyn (Monroe) shuts the door, saying, “Oh, don’t look at those, they’re nothing. Gay just had them up for a joke.” Monroe would later say about husband Arthur Miller’s script, “He could have written me anything, and he comes up with this.”

Most tales of Marilyn play up her tragedy and supposed helplessness, however, it is significant to note that Marilyn fought for and eventually got influence both over her scripts and selection of director. Photographer and friend Sam Shaw said: “She laid the laws down…She became a tyrant as a producer, a big tycoon trying to lay the law down to the Hollywood bigshots.” Her difficulties on set are well documented but never fully explained. Perhaps Marilyn’s repeated requests for re-takes were merely a way for her to assert her creative vision onto a production? One scene of Some Like It Hot reportedly took between thirty and eighty takes, depending on the source. It was a simple scene, where Marilyn merely had to say, “Where’s the bourbon?” while rifling through a drawer, her back to the camera. What goes unmentioned in most accounts is why Wilder could not simply have rerecorded the dialogue, looping it back during postproduction. As Sarah Churchwell notes, “his insistence on take after take…suggests that they were engaged in an overt power struggle…Her tactic seems obvious in retrospect: the only time she said ‘Where’s the bourbon?’ coherently, she also delivered the line the way she wanted to.” When Marilyn did pull off a scene in one take, it was as if to demonstrate that she could, in fact, do so—when she wanted to.

Today, celebrity and self-creation are bigger in America than ever before. Monroe played a pivotal part in this narrative, and we can see continuing parallels in more contemporary stars. Madonna, as noted by everyone, especially Camille Paglia, rarely takes a bad photo. At very least, she studied Marilyn Monroe and learned how to work the camera with similar flair.

While I cannot argue that Marilyn constructed herself as consciously as Madonna clearly has because I have no way of knowing for sure, certain things are clear. From this unique train-wreck of an emotional tableau emerges many things: an ease and flawlessness when being photographed for still images that cannot be sustained on film without suffering and inconvenience for all involved; captivating performances that occur as completely artificial but at the same time reveal greater honesty and vulnerability than anyone else with whom she shared the screen; and a mythology that she most certainly created but seemed unable to control. The difference between creation and control is something often collapsed in auteur theory. It is my hope, in illuminating the difference via Marilyn Monroe, that we can start to see the distinction more clearly.

One person I saw on a film blog criticizing Marilyn, wrote that she was divorced from Arthur Miller at the time immediately following the release of “Let’s Make Love”. Actually, Miller was, along with John Huston, readying “The Misfits” for her. She was ill during the filming of “Let’s Make Love”, as she was ill often for almost every movie she made; a little known fact about Marilyn is that she suffered from excruciatingly painful menstrual cycles, a taboo ailment which was never, ever discussed during the fifties, or hardly ever during the sixties or seventies, or even now, for that matter. As someone who has also suffered from that unique and debilitating condition, I can most definitely empathize. In a bizarre way it was strangely fitting that this woman, the ultra-example of the Eternal Feminine, should have to bear the ultra-symptoms of the “curse” of that femininity. She also had to have her gall bladder out towards the end of this movie’s production, which delayed the start of The Misfits by six months. A lot of rumors and bad-mouthing are thrown around about her as though they are fact– but folks, it could not have been easy to be Marilyn Monroe. She was one of a kind: she was otherworldly beautiful. She glowed (she was covered in a natural, golden down which caught and subtly diffused light). She was extremely intelligent and amazingly forgiving of a world that abused her as a child and ultimately murdered her as an adult. But her legend will live forever… Happy Birthday, beautiful, beautiful Norma Jean. And rest in peace, darling.

Monroe did indeed suffer tremendously from endometriosis–the extreme pain of her menstrual cycles were one of the reasons she became addicted, early on, to pain killers. However, Monroe’s gall bladder was removed in the spring of 1961, after the completion and release of both “Let’s Make Love” and “The Misfits.” The scar in the photo above was never meant to be seen by the public. Before Marilyn undressed for Bert Stern she asked, “But what about my scar?” Stern said, “Don’t worry, we’ll retouch it.” Only then did he agree to pose. Of course, soon she dead, and he totally disregarded his promise.