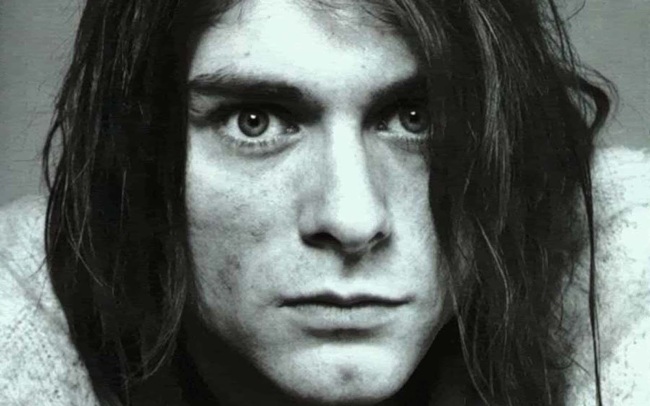

My memories of Kurt Cobain are complicated.

I remember being shocked by his death, thinking, in my high school naivete, that rock stars live forever, forgetting that “forever” is long after the abandonment of this mortal coil. I also knew that if I was shocked, many others would be too, and I immediately rushed to read a quick speech over the high school public address system. I must have written it in advance, because I can’t imagine I would do that kind of thing off-the-cuff, but there was little time for preparation, so I suspect I wrote it in on my way to the principal’s office. There was a moment of silence, which I insisted on, even though I knew how inadequate a moment of silence really was. But at least it felt like a symbolic acknowledgement, a carving out of time against the establishment I was sure Cobain hated far more than I did. I had enough authority, somehow, to ask for things like moments of silence, and so I got one, for him. And it felt like a victory.

But that moment has lasted twenty years. Kurt Cobain has never gone away. He has always lingered on the edges, not only in the legacy of who he was, but for the voice he gave to the voiceless, the anger and frustration he draped in music.

I remember my Nevermind cassette. I am surprised it lasted as long as it did, played over and over and over in my old Toyota Camry as I drove the streets of my bland suburbia, from the high school, where I felt misunderstood and unnoticed, to my home, where I felt more of the same, to the punk shows at DC’s Fort Reno, to the concerts at the old 9:30 club, to the goth/industrial nights at the Roxy and Tracks. My life seemed to be carved (mostly) of times when I did not belong versus those times when music made me feel like I did.

Music connected me to something larger. Music made me feel less like an outsider. Music made me feel like I was understood. The first time in my life I ever felt like I fit in was the first night I went to a goth club. It was not a matter of looking like everyone else — for someone as fascinated with performance as I am, it has always been easy to look however I want, but you are never as lonely as when you are in a crowd, especially a crowd that does not see you. It was a matter of feeling like I was not the freak or the odd one out. It was a matter of feeling included. I finally belonged.

Nevermind was one of those albums that made me feel like I belonged. First and Last and Always by the Sisters of Mercy was another. Also Burning From the Inside by Bauhaus and Warsaw by Joy Division. There were tracks that grounded me more than others, but it was always the music that helped me escape. It was music that provided solace. I was not alone. My people were out there.

And then Kurt was gone.

That was not supposed to happen. He was larger than life. He was an icon. He was a symbol. I forgot that he was also a person.

What tore me up was that music, the thing that had provided me with so much solace, the thing that he had given me, had clearly not been enough for him. It was a cruel irony. I wanted to return the favor and I could not.

I can still listen to “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and “Lithium” and “Polly,” and it is like time has not passed at all. I may not be as young (or as angry) but music still transports me. Music still connects me to a world greater than my own. Music is still my solace.

A couple weeks after Cobain’s suicide, I ended up on an MTV Town Hall with Bill Clinton. Somehow I was chosen to ask him a question. “Kurt Cobain’s recent suicide exemplified the emptiness that many in our generation feel,” I said. “How do you propose to change this mentality?”

Bill may have given me the usual political spin, (“Everybody needs to be the most important person in the world to somebody, and people need to think of . . . the real future, what happens years from now, not what happens minutes or days from now.”) but I did not care. He may not have understood how I felt, or what it felt like to imagine suicide as an escape, as a relief from the oppression of everyday life. But I did not care.

All that mattered to me was that, once again, I had managed to get the bureaucratic establishment to stop and pay attention. I had managed to get another moment for Cobain, for myself, for anyone out there who knew the pain of emptiness and not belonging.

The moment may have been fleeting, but for me, anyway, it has lasted twenty years.

Recent Comments