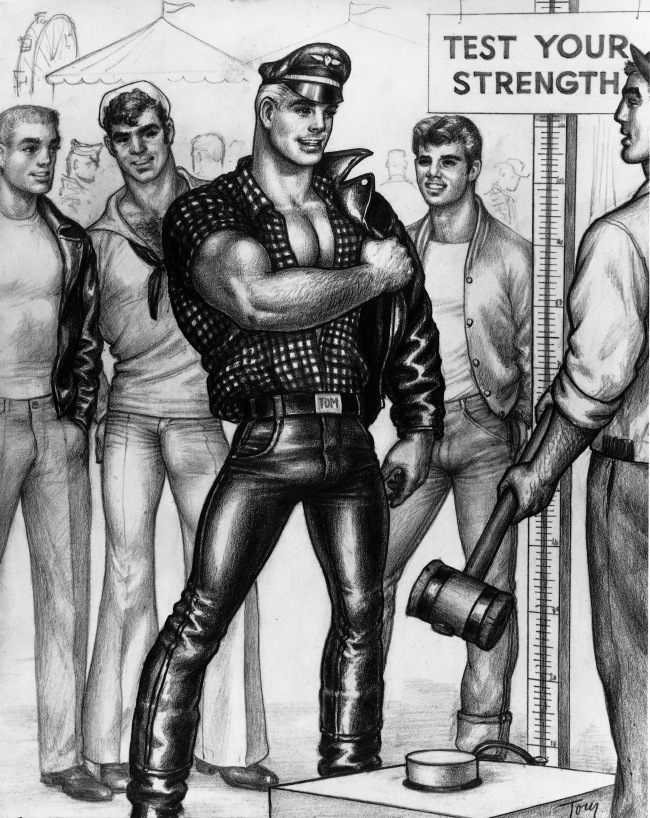

Tom of Finland, Untitled, 1962, ToFF Cat. #62.27, Collection of Volker Morlock, © 1962 Tom of Finland Foundation

There is a scene in Dallas Buyers Club where Matthew McConaughey’s character goes into a gay bar to conduct some business. As he’s standing in the bar, the camera pans around, and I’m pretty sure I saw a Tom of Finland image on the wall. It might not have been an actual Tom of Finland image, but it was definitely inspired by Tom of Finland, at the very least.

And that’s part of what makes the current exhibition at MOCA so fascinating. On one level, it feels like kitsch, because these images have become so ubiquitous, we forget where they all began. We forget where the gay movement began. We forget just how political it once was to put a Tom Finland poster up on the wall, just as we forget how political it was (and in many places still is) merely to be gay.

Wandering around the show, surrounded by pin-up style images of naked and nearly naked men, the show has a fun, lighthearted quality. It is not burdened with the comprehensive heaviness of a retrospective. Rather, it is focused on images chosen by the curators, including some of the less known catalogue work from Mizer and Tom’s work from the sixties. Strong beefy men drawn by Tom of Finland or photographed by Bob Mizer. Heavily sexualized men. Fun, playfully kinky men. Gorgeous hunks of men. A tribute to camp of which Susan Sontag could be proud.

Tom of Finland, Untitled (1 of 4 from “Circus Life” series), 1961

Bob Mizer/AMG Collection, Tom of Finland Foundation Permanent Collection #61.11, © 1961 Tom of Finland Foundation

As Sontag writes in her infamous essay “Notes on Camp,” the essence of Camp is “its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration,” and these hypermasculine men, posed beefcake style and accessorized with leather and bondage gear, reek of exaggeration. Sontag also argues that “what is most beautiful in virile men is something feminine,” and here, too, she is right. There is a sensitivity, a softness, in the way these men are drawn and posed, with an eye for detail and style that is arguably feminine. These men are pin-ups, and yes, these men could be performing life as theater. They are, after all, performing masculinity.

The exhibit not only includes Tom of Finland’s drawings, the finely rendered graphite and pen-and-ink drawings for which he is known, but also his collages, which were intended only for his own private use. These collages became essential components in Finland’s artistic process, categorizing and displaying expressions, postures, costumes, and body types which he would go on to use in his drawings.

Despite the cartoonishness and explicit sexuality of these images, a delight in rough, raw, and explicit manliness, there is a seriousness lurking around the edges of the exhibit itself, an edge that grounds and reminds that all is not just fun and frivolous here. Beneath the decadent surface, there is the nagging reminder of what these images stood/stand for. Tom of Finland reportedly required that there be at least one person laughing or smiling in his images because most gay men were portrayed as unhappy. Tom wanted (needed) to show sexual empowerment and confidence and happiness. To rebrand gayness, if you will.

There was a politics to his playfulness. An all-too-serious agenda. A determination to dispense with negative stereotypes of what homosexuality looked and felt like.

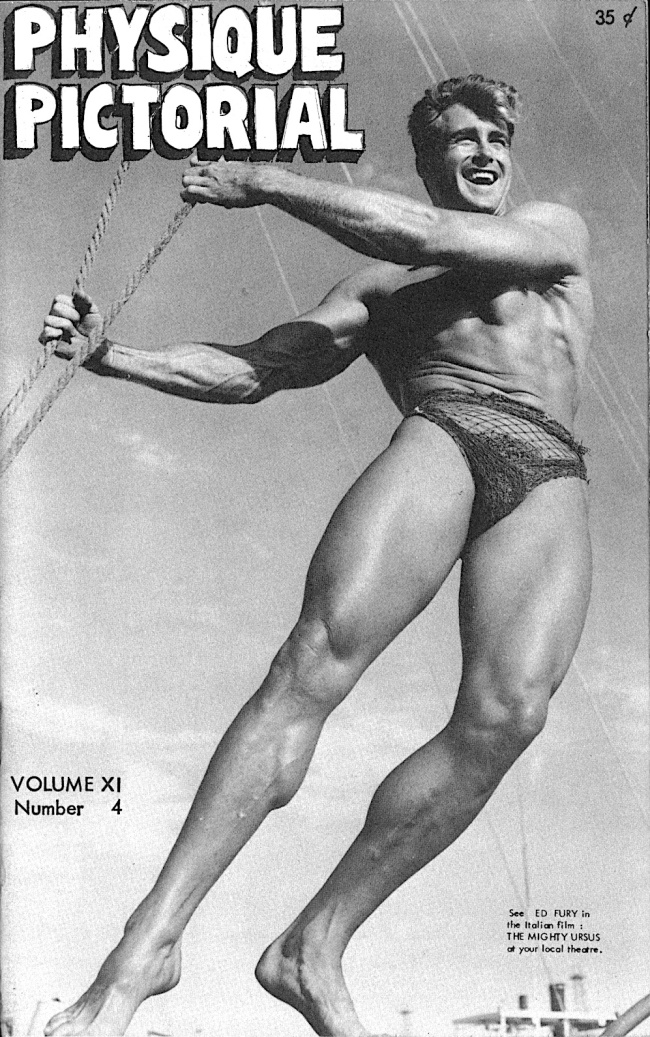

Bob Mizer, Physique Pictorial Volume 11 Number 4, May 1962, Publication

Printed with permission of Bob Mizer Foundation, Inc.

Mizer’s agenda, in turn, was so serious that he was sent to prison for it. Convicted in 1947 for distributing his own photos through the mail (the images of young bodybuilders was deemed obscene), Mizer served nine months—but those nine months did not deter him. Upon release, he continued his work, going on to amass a collection of nearly one million different images, not to mention thousands of films and videotapes. He created a literal beefcake empire.

Both Mizer and Touko Laaksonen, better known as Tom of Finland, would prove to influence not only artists like Robert Mapplethorpe and David Hockney, but even the fundamental aesthetic of contemporary gay culture. They created a new vision of masculinity, and this exhibit is a testament to that vision. This, they said, is what gay men could look like. This is what men could be. For a culture besieged by prejudice, hatred, and HIV, this reminder proved retaliation for the very fragility of homosexuality.

Even in the twenty-first century, when gay men kissing on primetime television is delightfully commonplace on shows like Scandal or Nashville, we are reminded not to get complacent, to appreciate our relative American freedoms. There are states in America, much like there are countries in the world, who would prefer to see gay men disappear, which is why it is all the more extraordinary that, in a place like West Hollywood, a show about Bob Mizer and Tom of Finland could feel like no big deal at all.

And that is precisely why this show is such a very big deal.

This show may seem like it is merely about gay shamelessness, a lighthearted frolic in sexual perversion, but instead, at its core, it is a celebration of sexuality and freedom. And these days, as any scan of current events will remind us, putting the “sex” back in homosexuality is still a radical and even dangerous move.

Bob Mizer & Tom of Finland is on view at MOCA Pacific Design Center

(8687 Melrose Avenue, Los Angeles) through January 26, 2014.

Recent Comments